The Mexican Revolution (1910-1940)

The forces opposing Diaz began to coalesce in about 1905, and in 1906 revolutionaries attempted to overthrow the Diaz regime by organizing strikes at the Cananea copper mine and at the Rio Blanco textile mills. But those efforts failed.

Then Francisco I. Madero, a wealthy landowner and industrialist, but part of a group which had been excluded from power by the Diaz dictatorship, attempted to run for president; but Diaz had him jailed. Escaping from Mexico to the U.S., Madero then launched the revolution on November 10, 1910 with the slogan “effective suffrage and no re-election.” November 10 is still celebrated as a national holiday.

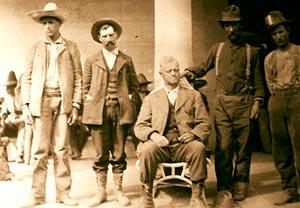

Madero’s revolution calling for democracy also attracted support of small ranchers and poor peasants who were fighting not only for democracy, but also for land. Pancho Villa in the state of Chihuahua in the north organized an army of small ranchers, railroad workers and miners, and other middle class and working class people. Emiliano Zapata in the state of Morelos in the south organized the poor peasants who demanded that the haciendas return the land to the peasant communities. Together Madero, Villa, and Zapata and other revolutionary forces succeeded in overthrowing Diaz. An election was held and Madero was elected president.

But Madero proved a weak leader who failed to satisfy anyone, and he was overthrown and murdered by the counter- revolutionary Victoriano Huerta. Once again the revolutionary forces rose, this time under Venustiano Carranza, Alvaro Obregon, Villa and Zapata, and once again they were victorious by 1915. But then the revolutionaries had a falling out, with the more conservative Carranza and Obregon and their Constitutionalist Army fighting against Villa and Zapata and their Conventionist forces.

The Constitutionalists won, with Zapata and later Villa being assassinated. Then Carranza and Obregon had a falling out, and Carranza was assassinated and Obregon and his allies took power. Obregon became president in 1920, ending the violent phase of the revolution.

The Results of the Mexican Revolution

The Mexican Revolution destroyed the old government and army of the dictator Porfirio Diaz, and eventually changed the country’s economic and social system in important ways. Between 1920 and 1940, particularly under President Lazaro Cardenas (1934-1940), the Mexican revolutionary government radically altered the economic and social system in Mexico.

First, the hacienda system was ended after hundreds of years as haciendas’ land was divided up and distributed to Indian communities and to peasants in the form of “ejidos.” Second, the Mexican government recognized the labor unions and peasants organizations, and promoted their organization, and their incorporation into the state-party. Third, Cardenas expropriated the foreign-owned oil industry (owned by Standard and Royal Dutch Shell) and created the Mexican petroleum company (PEMEX). Fourth, a new Mexican business class grew up more based in banking and manufacturing than in land. While Mexico remained capitalist, it now had a mixed economy, part state-owned and part Mexican and foreign private capital.

The Mexican Government Turns Right

After Cardenas stepped down as president, the Mexican government turned to the right and become much more conservative in economic terms. Mexico also became drawn into the Cold War, and in the late 1940s and early 1950s, Mexico saw an anti-Communist witch-hunt much like that in the United States. Communists and other radicals were purged from the government party, now called the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), and from the labor unions and peasant organizations. The Mexican government gradually became far more supportive of Mexican and U.S. capital than it was of Mexican workers or peasants. By the late 1950s, Mexico’s government had become an authoritarian state which suppressed popular movements to promote and protect capital.

Continue to next page: From the Mexican Miracle to the Mexican Mess »