Mexico’s labor law originated in the revolution of 1910-1920, producing the Constitution of 1917. Article 123 of that Constitution gave workers the right to organize labor unions and to strike. It also provided protection for women and children, the eight hour day, and a living wage. When written, it was the most progressive labor law in the world. However, it was not until 1931 that Article 123 found expression in national legislation in the form of the Ley Federal de Trabajo or Federal Labor Law (LFT) . By then, the Mexican state dominated by former president and power-behind-the-throne Plutarco Elías Calles had found inspiration in Benito Mussolini’s fascist state with its authoritarian corporate structure.

The LFT established the Juntas de Conciliación y Arbitraje (the Boards of Conciliation and Arbitration), made up of representative of the government, employers and labor unions. The state thus became the ultimate arbiter of labor relations, a role strengthened over time. The Secretary of Labor and the Juntas maintain a strict system of legal control over labor unions: unions must have a legal registration (registro), must have an officially recognized right to negotiate collective bargaining agreements (titularidad), and must periodically re-register their officers and be accepted by the state (toma de nota).

Why it’s tough to organize democratic Unions

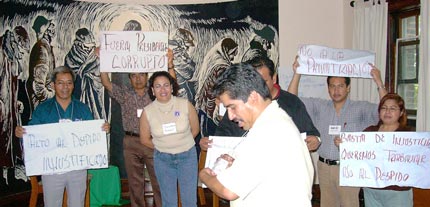

The system operates to the detriment of independent unions . Although this system of labor relations initially conferred real benefits on workers and peasants whose organizations supported the government, it now functions to maintain a status quo where benefits flow only to corrupt union leaders . Consequently, democratic unions must confront not only corporations, but the corrupt, official unions and in most cases the labor authorities as well.

This is because under the tri-partite structure described above, the seat of the representatives of labor is almost always filled by the largest of the official union federations — the CTM — the business representative will always oppose an independent union, and the presidency of the labor boards is held by the government — generally the PRI, occasionally the PAN, and only on very rare occasions by the PRD. This means that in virtually all cases at least two, and usually all three members of the labor board have a vested interest in seeing that the independent union loses.

There are also practices that severely interfere with a democratic union’s ability to navigate through the legal maze which it encounters. First, unlike the United States, a union must have a certification or registro before it is may legally represent workers in a particular workplace . While these are theoretically available by following a relatively simple administrative process, and in fact are available to the official unions in a matter of days or weeks, the pretexts for denying them to independent unions are, in the words of one democratic lawyer “as vast as one’s imagination.”

The second major obstacle is the practice by employers of entering into protection contracts with sindicatos fantasmas or ghost unions, often before a plant is ever built. Various groups, such as the National Association of Democratic Lawyers (ANAD) and the independent UNT estimate that between 80 and 90 percent of all contracts fall into that category. The system is so effective that it is extremely difficult for independent unions to obtain registros, win elections, or gain the legal right to represent workers.

What ‘Protection Contracts’ do

Protection contracts impede real unionization in several ways. The first is that these contracts usually contain only the minimum conditions with respect to wages, benefits, etc. required by Mexican law. Second, one of the clauses is generally what is called an exclusion clause – giving the union the right to instruct the employer to fire workers. Despite the fact that Mexican courts have held it unconstitutional to fire workers because they seek to organize a different union, this clause is routinely used for that purpose. As a consequence, one of the major differences in organizing in the United States and Mexico is that while U.S. unions often use public demonstrations of strength (use of buttons or stickers, petitions or demands for recognition) as a test of strength prior to petitioning for an election, in Mexico union organizing must be totally clandestine until the moment the legal petition is filed.

The third way in which protection contracts function to deter real unionization is that they make it legally much more difficult to organize: in Mexico different legal procedures apply depending on whether a union has already been certified. If there is no union, the workers who are seeking union representation file their proposed contract along with a strike notification. This puts the employer on notice that it must either accept the contract, negotiate something different or face a strike; it puts the union in a much stronger position than in the U.S. where we must first win an election and only then have the right to negotiate a contract.

If a union exists in a plant, the democratic challenger must file a petition with the labor board seeking an election to determine which union in fact represents a majority of the workers. Since the labor board is almost always strongly biased against the independent union, this usually results in interminable delays. And if and when an election is finally held, it will be by voice vote rather than secret ballot. Thus, workers will have to present their credentials to a representative of the labor board who will be flanked by multiple representatives of the employer and official union (and often union goons) and a limited number of representatives of the independent union. (The elections are generally held within the plants so the employer has the right to permit entry to the thugs and exclude all but a few representatives from the independent union). Finally, even if the independent union should win the election, the original contract remains in place until its expiration, locking the workers into an agreement based on what are generally the minimum requirements mandated by the federal Labor Law.

Information on unions and contracts kept secret

Another practice that serves as a major obstacle to independent union organizing is the failure to make registries of unions and contracts available to the public. When a union files a representation petition, it is required to follow one of the two legal paths outlined above, depending on whether a union exists in the work place or not. Where a union exists, the petition must contain its correct name, legal address, etc. A petition will be dismissed if the union has either chosen the wrong process (e.g. it thought there was no union when one had been certified) or where information such as the name and address of the incumbent union is inaccurate.

The danger is obvious: if the workers are unaware of the existence of a protection contract, they may file the wrong type of petition, it will be dismissed, and they will be exposed to discharge directly by the employer or at the behest of the union pursuant to the exclusion clause. The Alice in Wonderland character of these proceedings is illustrated by very real cases where the labor board dismisses a representation petitions because the name or address of the incumbent union which is being challenged is incorrect, when it is the government (and not the independent union which has filed the petition) which has exclusive access to the correct information through registries of unions and contracts which are not available to the public!

It also should also be noted that the Juntas typically declare strikes to be inexistente or non-existent, meaning that striking workers lose legal protections. Consequently, despite many labor protests and work stoppages, the number of legal strikes in Mexico has become negligible.

Rampant corruption

Finally, the system of corruption within the official unions is nurtured by the concentration of power in the position of general secretary, and the lack of transparency in union affairs and finances.